Thailand

Thailand: The Kayan in Limbo

Thailand: The Kayan in Limbo

Where: Thailand

When: 2022

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, up to 250 tourists a day could walk down the only paved street of the village of Huai Pu Kaeng, a village that became famous for the Kayan women who live there, better known as "Long Neck Women" because of their neck made very long by the brass spiral necklaces they wear.

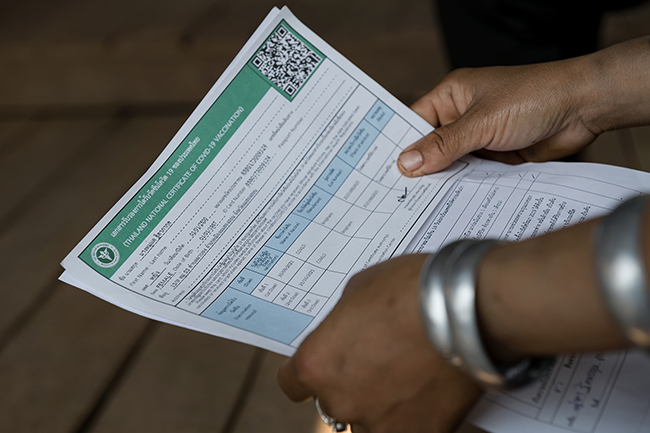

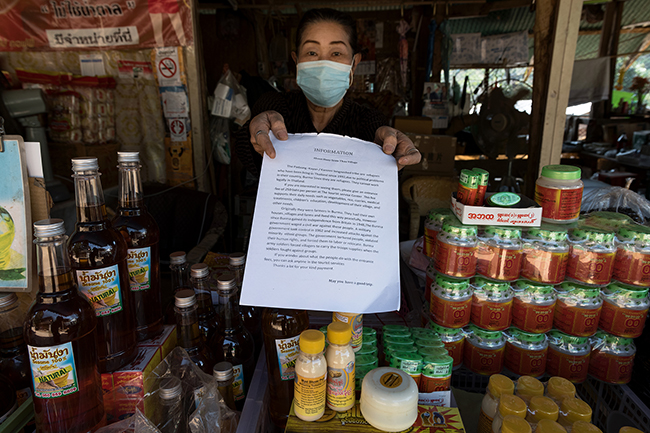

Today, the restrictions linked to the Coronavirus that were puted in place in Thailand to reduce the spread of the virus also reduced the flow of tourists to a mere trickle.

Even if small groups of tourists have been showing up again in the last few weeks and the Thai kingdom has relaxed its entry restrictions, the golden age of tourism in the village of Huai Pu Kaeng seems to be over. It is probably a necessary step for the Kayan women, who after arriving in Thailand as refugees, and after becoming the flattering stamp of a conquering tourism, will have to adapt once again to a new reality.

Without visitors for almost two years, the Kayan world has changed and left them in limbo.

May they now find their way into a different future.".

Full story, both in French and English, available on request.